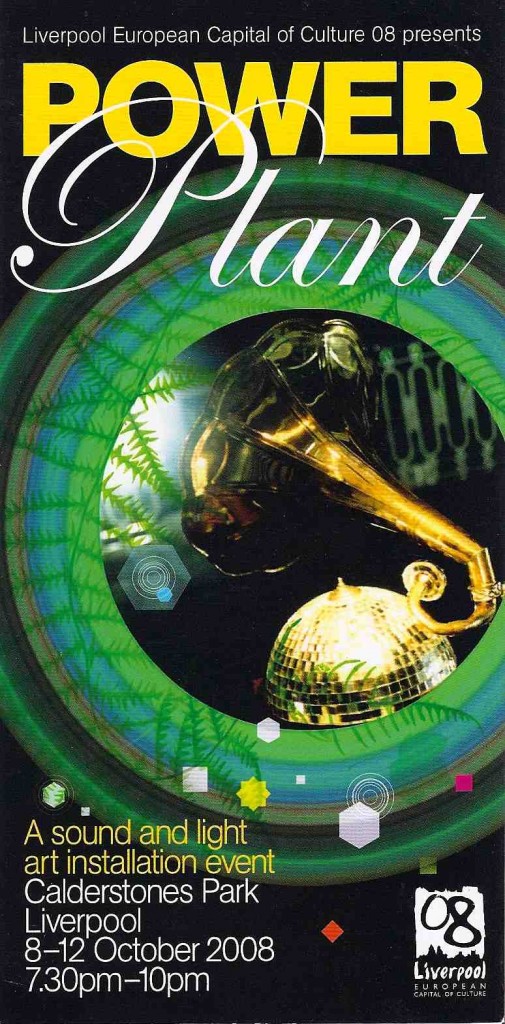

Power Plant

Started out designing some software for the boss, then was invited to contribute to the quadrophonic soundscape in the Japenese zen garden. A mind-blowing array of audio visual art works set in Palmerston Park, Liverpool, for the City of Culture 2008. One of the best things I have ever been involved with; now on tour around the world.

see the website here

Power Plant in Liverpool – the Sunday Times review

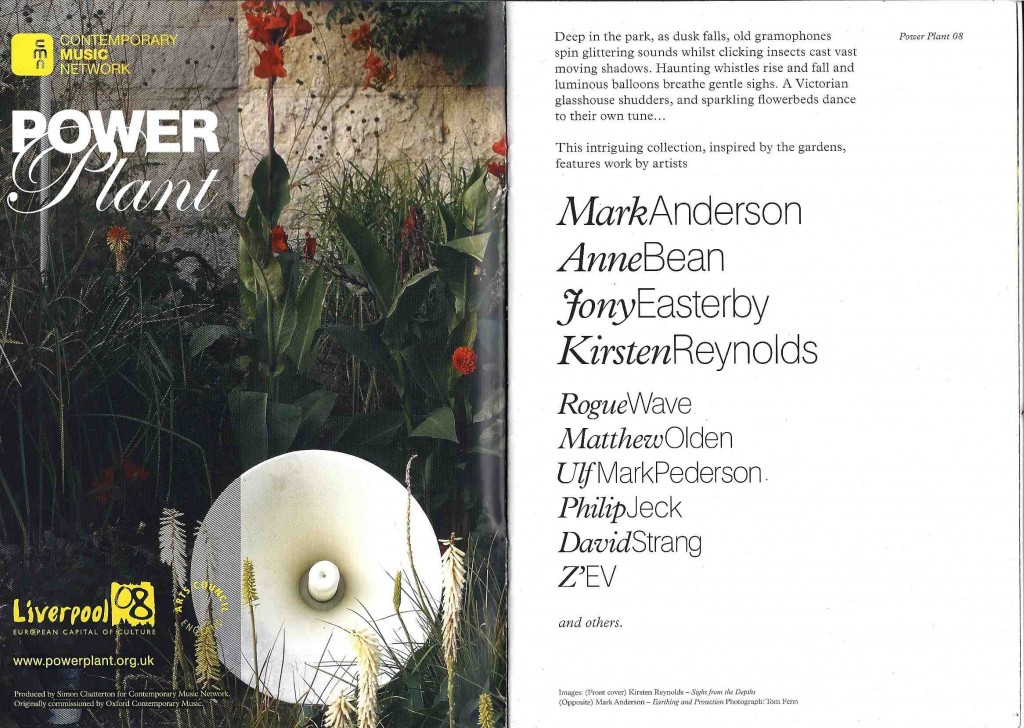

Calling your event a “sound and light art installation”, and asking the ordinary citizens of Liverpool to pay to watch it in a park at night, hardly seemed like a sure-fire way to pull in the crowds. Of the 10 featured artists, only the turntablist and distressed-vinyl provocateur Philip Jeck had much of a public profile, and on the night I went, the weather was about as uninviting as it ever is in south Liverpool in October. Remarkably, though, it proved a huge success. Sold out as it was on all of its five nights in Calderstones Park, Power Plant’s ingeniously playful array of electronic stunts, kinetic sculptures and musical sound effects sprang a series of delightful surprises. The first, for me, was Calderstones Park itself — once part of an aristocratic estate, it is well endowed with walled gardens, hot houses and exotic features that stood up beautifully to Power Plant’s eccentric son-et-lumière approaches.

Of these, the show stopper was Mark Anderson’s Pyrophones, an elaborate arrangement of metal pipes, topped with propane burners, that sporadically shot balls of flame into the night sky, to the accompaniment of what sounded like a lugubrious fugue for beaten-up foghorns. In a similarly populist vein, Jony Easterby’s Worm Cam projected kaleidoscopic images of live snails, slugs and worms onto a screen, rendering them as unrecognisably beautiful diagrams of shifting line and colour. While the kids flocked to this, their grandparents were enjoying Siren Song, a sound piece artfully constructed out of second world war air-raid sirens on and around a monument to a local dog that helped to rescue victims of the Nazis’ 1940 blitz on the city.

Much of the show was more enigmatic, infiltrating the park’s trees with lights and filling the air with ghostly noises. We entered to the sound of Wolves Whistle, featuring another of Anderson’s pipe ensembles, this one powered by old vacuum-cleaner motors, in which the partially illuminated nearby trees blared mournfully at each other. That theme was echoed by Kirsten Reynolds’s From Memory, where a row of lamp shades controlled, sort of, by dimmers fitfully engaged in squeaky electronic chatter (another of her pieces, Reflection, is pictured below). Anne Bean’s Breathing Space offered another haunting animation of things inanimate: a pile of palely lit, giant weather balloons, gently deflating into squidgy emblems of inevitable decay.

Power Plant is an enhanced version of an installation first put on in Oxford’s Botanical Gardens in 2005. Its interest in pyrotechnics and repurposing obsolete technology was upgraded for this event with contemporary widgets such as windscreen-wiper motors, gas-cooker igniters and sound-sensitive light wire.

The point of it all, for me, was to promote a sense of amused mystery at a world we partly inhabit, partly create and, for better or worse, endlessly mess about with.

The families who made up most of the show’s 1,500-strong audience on the night I visited loved it. Long before I perused the visitor-comments book on the way out — unanimously positive, especially from children such as Laura, 9, whose spidery inscription pronounced it “mind-melting” — Power Plant trashed the general view that abstract art and weird music are elitist pursuits designed to baffle the uninitiated. It will be a small tragedy if this show isn’t recommissioned elsewhere.

Leave a Reply